So, light is coming to us from the sun in waves, but what is it traveling on? Ocean waves are energy traveling in the medium of water, but light, which is also energy, is going through space, which is empty..."Hmmmm", says the mid-19th century physicist, "there must be something in space after all. Let's call it ether!" Which is kinda like saying to a man who just told you he talks with angels that he's hallucinating, which is really saying to him I don't know what the bleep is going on but if I give it a name I feel better. So everyone was feeling good about the ether theory until two guys in 1887, Michelson and Morley, did an experiment to prove there was no ether (trust me, it's complicated but the experiment worked). Suddenly, everyone was in a quandary - if light travels in waves, how does it do it in a vacuum?

Then, in 1900, the plot thickened. Max Planck, considered the father of quantum theory, proved that energy travels in discreet packets, which he called quanta. In other words, energy at the smallest level does not go up and down smoothly, but jerks up (or down) in little spasms, or jumps - quantas. And this is where Einstein comes in; taking a clue from Planck, Einstein created an experiment using photo-sensitive materials and showed, in a paper published in 1908, that when light was shined on these photo-sensitive materials it knocked off individual electrons, not in a wave pattern but in a scattered pattern. Einstein showed with this experiment that light was, in fact, individual photons, or quanta of energy, pummeling the photo-sensitive material like a barrage of photon torpedoes! (OK, Einstein didn't call them photon torpedoes. In the early years of the Star Trek TV series, they employed physicists to consult them on the science of the the future. Photon torpedoes, warp drive, etc., were all inventions of these physicists/consultants. There's a book on the topic, called "The Science of Star Trek").

Now comes the dilemma, or shall we say, the woo woo. Thomas Young proved that light travels in waves. Einstein proved that light is a particle. So what is it, a wave or a particle? Let's think back to Young's double slit experiment, and use it to create what is called a thought experiment; in other words, imagine a real experiment that we can't really do but which we can...imagine. Let's say we have that double slit thingy, and behind it a wall that the light hits after traveling through the slits. Now, lets cover one of the slits, say the right slit, and fire a photon toward the left slit (Einstein couldn't do this in his experiments, but today this is actually possible). The photon hits somewhere within that fuzzy circle on the back wall, possibly anywhere. If we fire enough photons toward the left slit they will eventually hit every point on that fuzzy circle, just as would have happened if we fired trillions of photons all at once at the left slit. Now, imagine everything going into very, very slow motion, except we are still quick as a bunny at the controls of the experiment. We fire a single photon at the left slit, but being quick as a bunny while the photon is slow as a turtle, we lift the cover off of the right slit just before the photon passes through the left slit. Guess what happens? The photon never, ever hits the area of the the dark bands that showed up in Young's original experiment. We try firing photon after photon through the left slit, but if the right slit is open NONE of them lands in those dark bands.

Sheesh! What's going on here? When only the left slit was open, the photon could land anywhere, but just by opening the right slit, the photon is absolutely prohibited from landing on one of the dark bands! How does it know the right slit is open? What, did it spend time at the photon Starbucks before it took off getting instructions saying "right slit closed, anything goes, right slit open, be discreet"? In other words, are light photons conscious? Do they have morals and ethics (this would put them one step above the average Wall Street stock trader).

This is known as the wave/particle duality, and is a big conundrum for physicists even today. It turns out, what light is depends on how we look at it (does this remind you of looking at art?). If we set up an experiment to measure waves, as in Young's double slit experiment, we see waves. If we set up an experiment to measure particles, as in Einstein's photo-sensitive material experiment, we see particles. Light is very accommodating to our desires! Woo Woo; who knew?

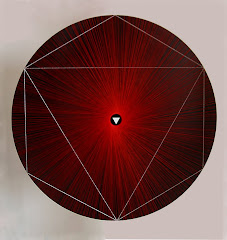

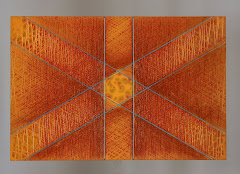

This is the beginning of a process, a becoming. My thoughts, feelings, sensations - long held close - now to slowly unfold like the petals of a flower, a lotus flower if you will. The lotus flower rises up from the mud of the murkiest pond, its roots deep in the muck as its petals open, floating on the surface, catching the waves of energy from our sun. From cold deep-dark moisture to warm, airy light - one continuous slow surge of being... becoming.

But enough of poetic musings! The chase is on!

But enough of poetic musings! The chase is on!

About Me

- Jeff Richards

- Denver, CO, United States

- Visual artist living and creating in Denver, Colorado.

Exhibitions

- Solo Exhibition - Sangre de Cristo Art Center Pueblo, Co 8/3/13 - 10/26/13

Followers

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(18)

-

▼

February

(7)

- Emanuel Swedenborg - Part I : Enlightenment Era Ma...

- Emanuel Swedenborg - Part II : Madness, or Rude Aw...

- Emanuel Swedenborg - Part III: Vision or Hallucina...

- Woo Woo part 1 : Waving Particles, Probably Like M...

- Woo Woo part 2 : Particles Waving...again, and aga...

- Woo Woo part 3 : Timely Waving Particles

- Woo Woo part 4 : Why Why Woo Woo?

-

▼

February

(7)

"Without Haste, Without Rest"

.jpg)