It's been more than a year since I've posted a blog, and after a long period of trial and travail in my outer life,which finally seems to be easing, the urge to turn to the written word has been stirring again. Unfortunately, getting back on the horse in such a rusty state of practice is no easy task, and the muse is not always available at one's beck and call. It would take a catalyst; and wouldn't you know, a synchronicity shot in out of the blue to jump start the tired engine. Love those synchronicities!

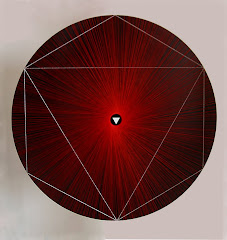

It went like this - I have an exhibition up through February 4, 2011 at the Pattern Shop Studio in Denver (check it out - www.patternshopstudio.squarespace.com/) and had sold an artwork to a friend, Margo, whom I had met through our mutual interest in the work of the philosopher Ken Wilber. One morning I was driving to her home to deliver the piece to her. Coincidentally (are there any coincidences, really?) a few days before I had been in the Denver library and happened upon the latest cd by Wilber, Integral Operating System, Version 1.0. I had checked it out and put it into my truck's cd player, listening in 10-15 minute stretches for a couple of days as I drove here and there on errands. Just as I approached Margo's address , delivery in hand, and pulled over to park, Wilber's voice on the tape asked rhetorically, "How does one uncover the meaning of a work of art through an integral approach?". I was flabbergasted! Here I was delivering an artwork to a Wilber fan, and out of the blue, at the very moment of my approach, his cd starts talking about...art! Sheesh!!

I immediately told Margo of this extraordinary co-incidence. And of course, we sat down over coffee and had a long talk about the meaning of the piece she had bought. Then I drove back to my studio listening to the answer to Wilber's rhetorical question on the cd, and at its conclusion I realized I'd found the inspiration for a new blog. The gods had not deserted me after all.

To put it in a very small nutshell, Wilber's integral philosophy is a model for understanding the occasions (as he likes to call them) of our experiences of life, one that calls for integrating many perspectives - that's a very, very small nutshell and I would encourage you to look into his writings. I was pleasantly surprised at how his approach toward finding meaning in art clarified and corroborated my own thoughts, but there was more to be explored here - namely, how does one create in the first place, especially when the meaning, much less the purpose, of the artwork is not always apparent to the artist him/herself (ok, maybe that's just one of my quirks, one not attributable to more competent artists)? So let's see how this looks under the lens of "Integral Thinking":

Let's principally talk about the visual arts since that's my area of creativity. What's the first thing you do when you're struggling with the meaning of an artwork? Why, ask the artist, dummy!!!!! Politely, of course - some artist's are a tad sensitive and thin skinned, and might start whimpering, while others may simply turn red in the face and stomp off indignantly. If you're shy you can read the artist's statement, but be prepared for some of the most awkward language you'll ever read - visual artists often choose that creative direction simply because words befuddle them (at least they're honest about their shortcomings - befuddle yourself and read serious art criticism in any of the major art magazines, written by people who are themselves befuddled by words but haven't figured that out yet). Nonetheless, if the artist is speaking with honesty and integrity you may indeed get profound insights into the meaning of the work.

Then again, the artist may be dead (try asking Leonardo what the Mona Lisa means and see where that gets you), in which case you might be able to research the artist's letters, or the writings of friends and acquaintances, to get an indirect hint as to the artist's intent. The important word here is "intention" - there's a school of art criticism that says that the artist's intention is the ultimate meaning of any work of art, and anything else imposed upon it from outside is just that, an imposition, one that lacks truth. This seems intuitively obvious, right?

But, but.....we all know that we (or at least everyone we know) have unconscious intentions, desires and impulses. In that case, can we really trust what the artist has to say? Is it possible that some of those unconscious intentions, desires and impulses slipped into the artwork unbeknowngst to the artist (after all, if the artist is unconscious of them she won't see them herself). This is where another school of art criticism arises, that of a psychoanalytic approach to understanding meaning in art. This gets a bit complicated since there are so many schools of psychoanalytic thought - you can take a Freudian approach and see unconscious sexual issues and the war between id and superego; a Jungian approach and see unconscious archetypes at work (I know an artist who describes her work as "mining the archetypes"); an Adlerian approach and see power issues at play; or any of the myriad approaches that have risen in the psychoanalytic world in modern times. All of these approaches are potentially valuable and can peel back layers of the onion. However, be wary - people using the psychoanalytic approach need to be very, very careful of their own unconscious agendas, their sneaky shadow that is waiting to trip them up and muddy their own interpretation!

These approaches into discovering the conscious or unconscious intent of the artist are, in Wilberian terms, the first person "I" approach - what's inside the mind of the artist at the moment of creation. Wilber's Integrative approach in fact defines four perspectives, or quadrants, necessary to consider the meaning of any occasion, including art. They are the "I" perspective, the "We" perspective, the "It" perspective, and the "Its" perspective. And indeed, there is a school of art criticism that takes the "It" approach, the "It" being the artwork itself, devoid of the intentions of the artist, conscious or unconscious - in other words, forget the artist, just look at the artwork and find the meaning there. After all, if it isn't there, it doesn't matter what the artist intended, does it - if its not there then the artist obviously failed to deliver his intention. So what is there, right in front of our eyes? There is form, there is color, there are symbols (sometimes), there are relationships of form and color and symbol. Let's call this school of art criticism...hmm.....Formalism? And the question here is, what is the "itness" of the work of art?

A bit dry, you say? Well, let me tell you a story of how the analysis of form reveals the heart of one of the great works of Western art....

To be continued...

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

Emperors, movements, and the challenge to just shut up

I know I said I was going to focus on the visual arts in this discussion, but now I must divert your attention to the musical arts, for it is here that some of the truly great works of Western Art arose - and I'm not talking American Idol! No, we need to go back a couple of centuries to the extraordinary music of Beethoven, and in particular to the composition I alluded to in a previous blog entry - Opus 111, his last piano sonata written only a few years before his death at the age of 56. A truly astonishing piece, and one that has a curious clue locked within its form, a clue that opens a door to meaning and intention within the work. And in this lies a clue to how the Formalist School, with its dry and materialist oriented "it" perspective, can be useful.

So what is the most obvious form that this sonata takes? Why, it's the sonata form, of course! And what is the sonata form? The form itself is very simple and general, consisting of 3 movements usually broken down like this - first movement, fast and energizing and gets-you-hoppin-in-your-seat; second movement, slow and introspective or romantic (sometimes downright schmaltzy); third movement, even faster and makes-you-wanna-run-outside-and-dance-in-the-streets. Composers adopted this form because it was popular and accessible and, heck, you gotta have some kinda form! And besides, it covers the basics - fast, slow, faster. And it's versatile in that it can be applied to any solo intrument or ensemble of instruments. Mozart was a wizard with the sonata form, but it was Beethoven who truly stretched it to its limits, and beyond.

(An aside.... one of Beethoven's most popular compositions in his time was his "Emperor Concerto", a concerto consisting of a solo piano accompanied by full orchestra. At the time Europe was emerging from the bloody chaos of the French Revolution, Napolean having managed to bring a semblance of order to the trauamatized French nation, allowing its neighbors a sigh of relief. Beethoven, like many, saw Napolean as a great hero, and dedicated this work to him - thus, the "Emperer Concerto". The form of the concerto was the sonata form with its typical three movements - fast, slow, faster. The premiere performance was given in the general atmosphere of exuberance and celebration at Napolean's feats, and indeed the third movement was not only faster, but literally got the crowd in attendance dashing out into the streets dancing and screaming WOOOOOOOOOOOOOHOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!!!! Later, when Napolean showed his true colors and became a dictator, Beethoven had the dedication removed from the transcript, but it was too late and the title stuck in the popular mind.)

So now, back to Opus 111...solo piano, the first movement is not only fast, it crashes down on you

like an avalanche. Think of an early nineteenth century version of a punk rock concert, the kind of music that has you hopping crazily, your head pounding up and down and eliciting an urge to dive headfirst into a crowd (with elegance of course; it is the nineteenth century after all). This is the music of a man with a mission, and with lots of anger fueling it. It's relentless, driving, unstoppable.... and it doesn't let up, slowing down just a tad only to gather itself for the next wave of hurtling energy that snatches you up and flings you like a bug. Ten minutes it goes without rest...and then, it suddenly winds down and drops you gently at your table, slumped in your seat breathing hard, sweat soaked and exhausted.

It's in that altered state created by the trauma of the first movement that Beethoven knows he truly has you at his mercy, for now, after a few silent moments, the sweetest, most angelic tune you've ever heard ripples gently into your consciousness, and an involuntary shiver of happiness nestles into a soft smile. The music is slow, it's easy, it's like being rocked by your mother. It's an aria, literally a song, a lullaby, indescribably comforting. The second movement has begun, and the form Beethoven will take here is that of the theme and variations, much as contemporary jazz musicians might improvise variation on a popular tune. From this lovely lullaby he moves into a lilting gait, a whistling stroll on a country path, then to a skipping frolic, then a mad exuberant laughing dash down that very path...and then, we are no longer running, we've lifted off the ground into the air, dipping and spinning and swooping with impossible freedom, pure joy in flight....and then....this is indescribable, but the music suddenly transforms and now we're in the heavens, the celestial sphere, weightless, out of body, and we're listening to the whispers of eternity, and we are no longer our solid body, our petty fears and anxieties and ambitions and plots and anger and sorrow....and then, we are not listening to eternity, we are eternity.....

And then...the music brings us back, back in our bodies, nestled in our mother's arms, in the arms of this manifest, lovely, wonderful world, and the aria returns, repeating itself in that original moment, until it simply...ends.....with a heavenly radiance and the softest earthly smile.

And that's the end of the sonata. No third movement, no dancing in the streets. Beethoven sent the manuscript to his publisher, who promptly sent it back, asking how he had so stupidly forgotten to include the third movement in the envelope. Beethoven simply replied, it's finished. That's it. Finito. And that was his last piano sonata. And that was the end, for all intents and purposes, of the sonata form.

So what does Beethoven's use of form tell us? It tells us exactly what he told the publisher - there is no need for a third movement, there is no need to dance in the streets, there is no need to blindly follow the convention of form, or of expectation, or of whatever you think you want to happen. In that incredible second movement he said it all, and shut up.

So what is the most obvious form that this sonata takes? Why, it's the sonata form, of course! And what is the sonata form? The form itself is very simple and general, consisting of 3 movements usually broken down like this - first movement, fast and energizing and gets-you-hoppin-in-your-seat; second movement, slow and introspective or romantic (sometimes downright schmaltzy); third movement, even faster and makes-you-wanna-run-outside-and-dance-in-the-streets. Composers adopted this form because it was popular and accessible and, heck, you gotta have some kinda form! And besides, it covers the basics - fast, slow, faster. And it's versatile in that it can be applied to any solo intrument or ensemble of instruments. Mozart was a wizard with the sonata form, but it was Beethoven who truly stretched it to its limits, and beyond.

(An aside.... one of Beethoven's most popular compositions in his time was his "Emperor Concerto", a concerto consisting of a solo piano accompanied by full orchestra. At the time Europe was emerging from the bloody chaos of the French Revolution, Napolean having managed to bring a semblance of order to the trauamatized French nation, allowing its neighbors a sigh of relief. Beethoven, like many, saw Napolean as a great hero, and dedicated this work to him - thus, the "Emperer Concerto". The form of the concerto was the sonata form with its typical three movements - fast, slow, faster. The premiere performance was given in the general atmosphere of exuberance and celebration at Napolean's feats, and indeed the third movement was not only faster, but literally got the crowd in attendance dashing out into the streets dancing and screaming WOOOOOOOOOOOOOHOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!!!! Later, when Napolean showed his true colors and became a dictator, Beethoven had the dedication removed from the transcript, but it was too late and the title stuck in the popular mind.)

So now, back to Opus 111...solo piano, the first movement is not only fast, it crashes down on you

like an avalanche. Think of an early nineteenth century version of a punk rock concert, the kind of music that has you hopping crazily, your head pounding up and down and eliciting an urge to dive headfirst into a crowd (with elegance of course; it is the nineteenth century after all). This is the music of a man with a mission, and with lots of anger fueling it. It's relentless, driving, unstoppable.... and it doesn't let up, slowing down just a tad only to gather itself for the next wave of hurtling energy that snatches you up and flings you like a bug. Ten minutes it goes without rest...and then, it suddenly winds down and drops you gently at your table, slumped in your seat breathing hard, sweat soaked and exhausted.

It's in that altered state created by the trauma of the first movement that Beethoven knows he truly has you at his mercy, for now, after a few silent moments, the sweetest, most angelic tune you've ever heard ripples gently into your consciousness, and an involuntary shiver of happiness nestles into a soft smile. The music is slow, it's easy, it's like being rocked by your mother. It's an aria, literally a song, a lullaby, indescribably comforting. The second movement has begun, and the form Beethoven will take here is that of the theme and variations, much as contemporary jazz musicians might improvise variation on a popular tune. From this lovely lullaby he moves into a lilting gait, a whistling stroll on a country path, then to a skipping frolic, then a mad exuberant laughing dash down that very path...and then, we are no longer running, we've lifted off the ground into the air, dipping and spinning and swooping with impossible freedom, pure joy in flight....and then....this is indescribable, but the music suddenly transforms and now we're in the heavens, the celestial sphere, weightless, out of body, and we're listening to the whispers of eternity, and we are no longer our solid body, our petty fears and anxieties and ambitions and plots and anger and sorrow....and then, we are not listening to eternity, we are eternity.....

And then...the music brings us back, back in our bodies, nestled in our mother's arms, in the arms of this manifest, lovely, wonderful world, and the aria returns, repeating itself in that original moment, until it simply...ends.....with a heavenly radiance and the softest earthly smile.

And that's the end of the sonata. No third movement, no dancing in the streets. Beethoven sent the manuscript to his publisher, who promptly sent it back, asking how he had so stupidly forgotten to include the third movement in the envelope. Beethoven simply replied, it's finished. That's it. Finito. And that was his last piano sonata. And that was the end, for all intents and purposes, of the sonata form.

So what does Beethoven's use of form tell us? It tells us exactly what he told the publisher - there is no need for a third movement, there is no need to dance in the streets, there is no need to blindly follow the convention of form, or of expectation, or of whatever you think you want to happen. In that incredible second movement he said it all, and shut up.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)